Architecture Community Experiences a Noticeable Impact on Mental Health Since Pandemic

Uncertainty about the future was top of the list of what is impacting Architecture Communities mental health. A loss of social life and/or work culture had the highest number of responders. Of 122 responses 87 reported they had not received mental health assistance and/or resources from their employers or schools.

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended life for billions of people around the world, ushering in a new era of uncertainty and dread amid a new global public health and economic crisis.

For members of the architecture and design community, the crisis has presented a host of professional and personal challenges: over a matter of weeks, many in the design community had to scramble to recreate their school or office environments at home, with the sudden loss of camaraderie, childcare, daily structure, and other supportive elements disappearing practically overnight. Many university students had to vacate campus housing, often returning home to time zones far removed from those of their educational institutions, as coursework, reviews, and eventually, graduations and end-of-year celebrations moved completely online. For those in the workforce, the rush to establish new work from home setups brought with it the added complications of financial uncertainty, as projects encountered construction stoppages and design delays while firms initiated painful staffing and pay cuts amid deteriorating economic conditions.

This is the first economic downturn I’m experiencing as an employee since finishing graduate school – worry about how this will shape the trajectory of my career and short term career goals that I had

Not only that, but the steady stream of bad news and mounting deaths, coupled with an atmosphere of deep economic, political, and social uncertainty in the face of the American government’s failed response to the emergency, has made enduring through these months particularly difficult for everyone, especially those who were not lucky enough to be able to work from home. At least 115,000 Americans have died—with minorities and low-income people impacted disproportionately from the disease—though the number is likely far higher and is poised to continue to grow for the foreseeable future. Meanwhile, more than 47 million Americans lost their jobs between March and June of this year, a modern record.

These historic events have rocked the country—and architecture—to its core, right down to the level of individuals, many of whom are grappling now with the stress of figuring out how to juggle multiple roles and responsibilities all at once amid the wider tumult.

Predictably these conditions have impacted our mental health rather broadly. In an effort to better understand how the emotional well being of the architecture community has been impacted by the crisis, we created Archinect’s COVID-19 Mental Health Survey, collecting responses in late May 2020 after roughly three months of quarantine.

The results of Archinect’s COVID-19 Mental Health Survey highlight the community’s struggles with the emotional impacts of the health crisis in some striking detail and show, generally speaking, that members of the architecture community have had a difficult time with the many challenges brought forth by the pandemic.

After collecting 125 responses and digesting the data, a few salient points have become quite clear.

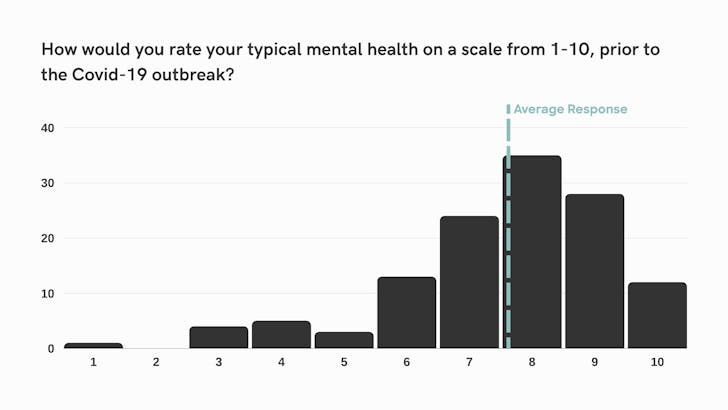

Mental health has deteriorated over time

To start off, the survey asked respondents to report their typical mental health prior to the pandemic on a scale from 1-10, with 10 representing a highly positive outlook. Of the 125 responses, 79% reported an initial score of 7 or higher, with the highest proportion of individuals, 28%, reporting a score of 8. Aside from the 10% of respondents who reported a score of 6, relatively few reported scores of 5 or lower at this point in time. For question one, the average mental health score fell at 7.57.

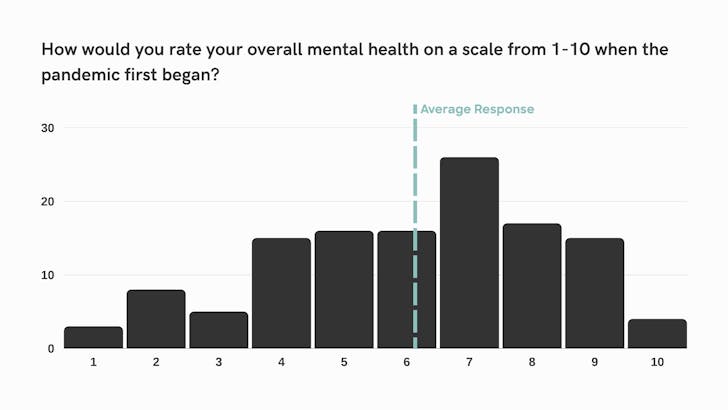

We see the distribution of responses trend downward almost immediately once the pandemic hits the United States in mid-March, however.

Working from home is very difficult when I also need to oversee the daily curricula for my two grade school age children. I cannot continue in this manner, and I don’t know what relief (if any) summer will bring.

Meanwhile, the number of people reporting scores 6 and below swelled, with 13% reporting a score of 6, 13% reporting 5, and 12% reporting a score of 4. While no respondents had reported a score of 2 to the first question, 6% did for the second, with 2% reporting a score of 1. Overall, for question two, the average mental health score was 6.10.

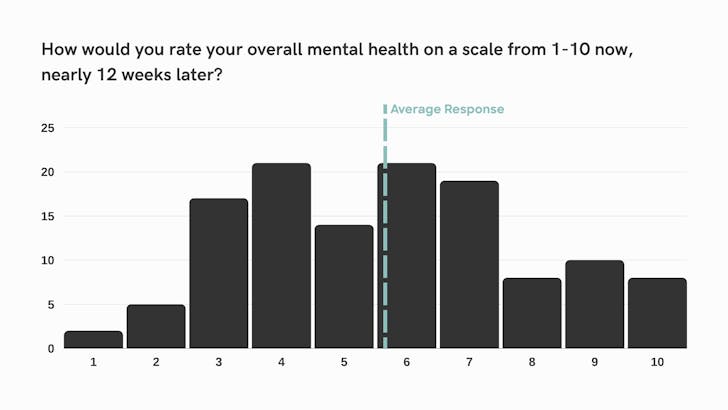

Responses to question three, which addresses the relative mental state of respondents after 12 weeks of lockdown, fell further.

Here, a sizable majority—64% of respondents—reported scores of 6 or lower. A sliver of good news for those in our community however, can be found in the fact that these responses tended to meet at the middle, with scores of 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 posting both a similar number of individual responses as well as the largest share of responses overall. The number of people responding with scores of 1 or 2 decreased, while those reporting scores of 3 or 4 rose sharply, for example, perhaps indicating that while the outlook for many continued trending downward, those reporting scores at the very bottom of the scale improved in their outlooks at least somewhat. For question three, the average reported mental health score was 5.68, nearly three points lower than the average answer for question one and about a half point lower than the average score for question two.

These responses indicate that while local, state, and federal governments began a push to “re-open” various sectors of the economy, many in the Archinect community saw little to celebrate as the country’s death toll surpassed 100,000 and the temporary solutions to the new problems created by quarantine life failed to deliver a sense of stability or normalcy.

I am very blessed to be in my position. Our firm is faring better than most due to our client base. So far, we have not had salary deductions or layoffs/ furloughs. While that still may be a possibility in the future, we are stable currently

Future uncertainties loom large

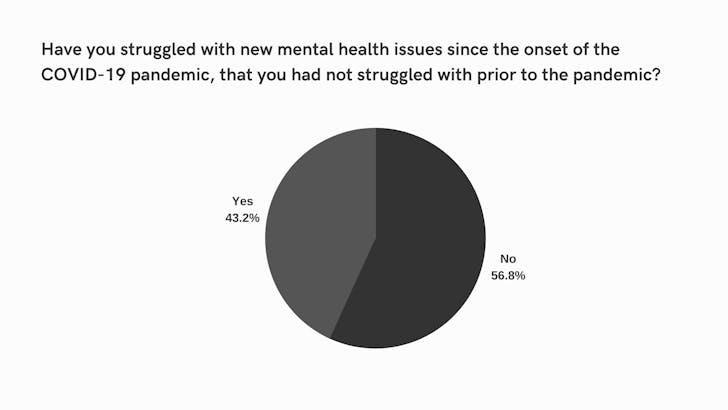

The survey’s next question asked more simply: Have you struggled with new mental health issues since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic that you had not struggled with prior to the pandemic?

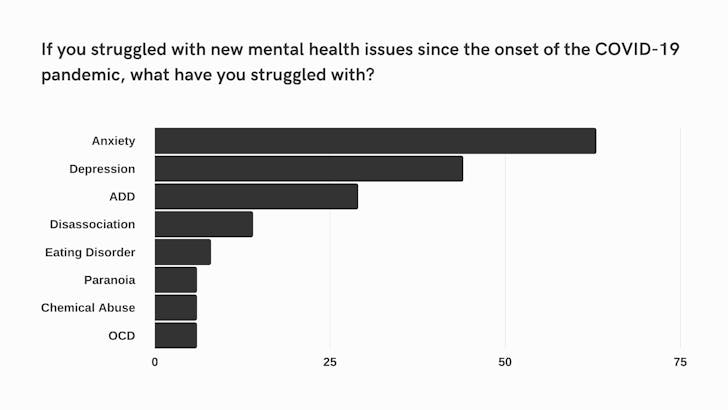

The majority, 56%, responded yes. Of the initial 125 responses, 76 who responded “yes” opted to share what some of these new struggles might be. This question, allowing respondents to select more than one answer, registers a significant rise in anxiety, depression, and difficulty concentrating among those who chose to answer.

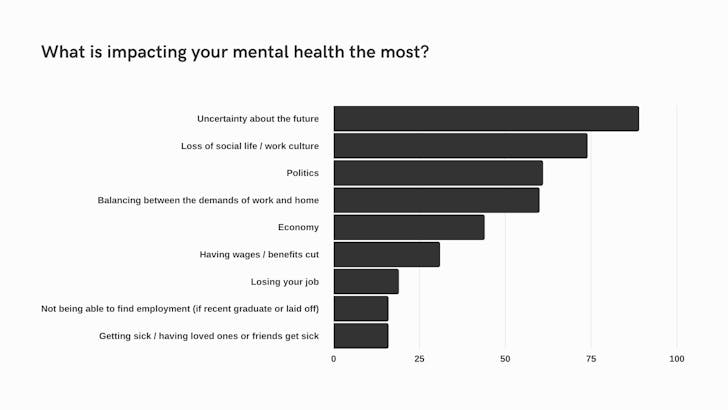

When asked what was impacting mental health the most, 121 respondents, allowed to select multiple responses, offered a range of concerns, with uncertainty about the future collecting the highest number of responses, 89. 74 cited a loss of social life and/or work culture as a significant contributor to mental health issues, while 61 indicated that the nation’s political troubles were a cause of concern. 60 people cited balancing the demands between work and home life as a significant stressor while 44 highlighted the state of the economy as a reason to worry. 31 reported worry over having their wages or benefits cut while 19 are worried about losing their jobs.

“I’m worried about how long this will impact the profession and, in turn, my own career as someone just starting out.”

With an understanding that worries for the future could be driving anxiety, we asked what it was specifically about the future that concerned survey respondents. This free-response question brings to light several issues, particularly that the unknown duration of the pandemic is driving anxiety among many people, and that a significant number, especially younger respondents, have a difficult time accepting the idea of yet another economic downturn just as their careers were getting off the ground.

“This is the first economic downturn I’m experiencing as an employee since finishing graduate school – worry about how this will shape the trajectory of my career and short term career goals that I had,” explains one respondent.

“I graduated from my master’s program in December,” explains another respondent, adding, “I moved to a new city with the hopes of increasing my chances of finding employment. I was very close to securing a position when hiring froze. I’m worried about how long this will impact the profession and, in turn, my own career as someone just starting out.”

“The possibility of having the career I have sacrificed over a decade of my young adult life to build, destroyed by systemic collapse. Nights and weekends spent in the office instead of with family and friends will never come back,” one person writes.

I question if I’ll be able to find my place in the post pandemic world

For others, the pressure and stress of navigating work and family commitments amid the pandemic presents a source of great concern and difficulty. “Feel like I’m sacrificial for the benefit of others; family, work,” one person explains, “Generally just feeling used for what I can do for ‘them’ without consideration about what I want out of life. It just feels like I’m stuck and my future is not my own unless I shed myself of those who depend on me; which goes against who I want to be. So… I zombie; get up, go to work, go home, do chores, sleep, and repeat.”

Another respondent supports this view, writing, “Working from home is very difficult when I also need to oversee the daily curricula for my two grade school age children. I cannot continue in this manner, and I don’t know what relief (if any) summer will bring.”

Others report an inability to envision how their work as architects might go forward. One person writes, “No idea how to be an architect anymore, how to take on these new challenges that are playing out in space, and how to face the issues of economic inequality, social inequality, and injustice, that we should be solving.”

“Speaking about my personal future, not our collective future,” one person adds, “I’m concerned about my ability to find meaning in my work, advance my career under my current garbage employer and working circumstances, care for and economically support my family, and contribute something of measurable social value in a time where that’s far more necessary than marketing another high-rise.”

For others who might be doing fine now, economically speaking, the potential that the slow-burning coronavirus situation goes on for months or even years is a cause for concern. “We still have work, but because there is usually a lag effect with architecture (at least, there is where I live, in New Mexico), I’m more worried about my community in the near term and our having work a year or so from now,” one designer writes.

One respondent offered a positive outlook: “I am very blessed to be in my position. Our firm is faring better than most due to our client base. So far, we have not had salary deductions or layoffs/ furloughs. While that still may be a possibility in the future, we are stable currently.”

“Right now I leave everything in the hands of God,” one person states simply.

“JUST KEEP SWIMMING,” writes another.

“I question if I’ll be able to find my place in the post pandemic world,” another respondent writes.

How to deal?

While mental health issues are not purely a personal problem or something that can be resolved through individual means alone, due to the nature of the quarantine and pandemic period, many have taken to personal activities to help soothe their stresses.

Among the most popular activities in this effort, according to the survey responses, are exercise, yoga, meditation, and engaging in unstructured activities, like spending time with family, playing video games, and partaking in personal hobbies.

“I’ve been exercising, reading, stress baking, and focusing a lot more on my 2 kids,” one person explains, “They’re 2 years apart at 2 & 4. When my thoughts start going down the rabbit hole, I go to them to help me pull myself out of it.”

During work, I have tried to call colleagues in order to talk rather than just sending emails

“Went back to painting, trying to be hopeful,” explains another.

“I try to take a lunch break at the same time daily and enjoy it outside in the sun. Often on weekends, the ability to drive (a privilege, I recognize) out of the city and through the countryside has been important for resetting my personal mental health – all the while observing the best practices of social distancing,” someone else writes.

For others, a simple, more personalized shift at work has helped too, “During work, I have tried to call colleagues in order to talk rather than just sending emails,” explains one person.

For some, a change in daily activities has helped, too: “Expanded prayer and meditation time, walking 3 miles a day, added several food gardens to our house lot, regimented up in early daylight, bed by midnight,” shares one respondent.

But even these rejuvenating activities can exact additional tolls when added to the increased stresses of working remotely, however. For example, one respondent said, “Trying to exercise or at least get out to walk. Trying to stay virtually connected with Family and Friends,” adding, “but after a day on zoom calls its exhausting.”

Went back to painting, trying to be hopeful

This has not, however, been the case for all, as some have been able to thrive in the remote work situation.

One respondent, for example, explains, “Working from home has been a huge benefit. I’ve been able to work on my own schedule and take breaks/walk around the block as needed to regain clarity without the watchful eyes of colleagues making judgements. This has enabled me to work more efficiently and be considerably more productive.”

“Actually, I feel much better getting to work from home, no 2 hour commute,” explains another respondent.

Help is not being offered

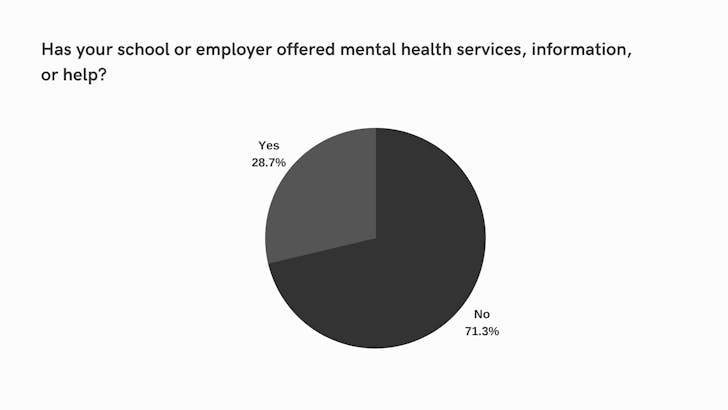

One of the more troubling statistics that has come out of the survey is that many people are not being offered help by their employers or schools with regards to mental health services or information.

Of the 122 responses to the survey’s final question, 87 reported that they had not received mental health assistance or resources from their employers or schools.

The response to this question perhaps illustrates one of the reasons why respondents saw such a significant degradation in outlook over the initial 12-week quarantine period: With compounding stresses and few resources or avenues for rest and relaxation, it makes sense that many would see their sense of happiness decrease.

With the pandemic showing no sign of abating and new social unrest stemming from the inequities the pandemic has exposed and exacerbated creating further uncertainty in the United States, this issue is not due to go away any time soon.